Realizing "A Dream Deferred": The Time is Now to Look Racism in the Eye

I didn't know I was black until I was informed of my blackness by a first-grade classmate at a small, private school in Charleston, South Carolina. Before that, it never occurred to me that I was different. I was quite confident for a six year old - saying to those who told me I was pretty, "I know!" I knew my hair was curly. I knew I could tell a good story and captivate my listeners. I knew, even then, that I was a leader, often finding myself in trouble for being the mastermind behind my friends' mischievous actions. I loved to talk and was unable to whisper. It never occurred to me then that others looked at me and judged me for my complexion.

A few years later, my parents enrolled me in a magnet school. Unlike my private school, where I was the only non-white student in my class, the magnet school was more integrated. At the start of the year, a student turned to me during a game of four-square and loudly announced to all of our friends - "you need a nickname … I'm going to call you Oreo." I smiled. Everyone else laughed. Oreos were my favorite cookies, so it made sense to me. When I got home, I proudly announced my new moniker to my parents. I will never forget the look on my mom's face - immediate shock that drifted into horror and then anger.

For many reasons, I was only enrolled in the magnet school for one year. I then spent 5th through 12th grade at the premier private school in Charleston where I was one of only two black students in my class. In those years, I was constantly reminded that I was inherently different than my classmates and friends:

"I don't really think of you as black."

"You talk white."

"Why is your hair like that? How many times a week do you wash it? Can I touch it?"

"You are a college's dream - good grades and black!"

"Stop worrying about college - you checked black on your application, right?"

"Well of course you got into Yale, you were the token black girl from our high school class."

"Would you like to pick the music? You must love rap!"

"Maybe you can explain why democrats …"

These types of experiences expanded beyond school. I was once followed around an Ann Taylor Loft for twenty minutes by a sales associate. The store was packed with customers but only had three sales associates - two of which were behind the counter and the one remaining proceeded to follow me from display to display. At first, she attempted to hide that she was spying on me by folding the clothes near me. As she followed me from rack to rack, her hawk-eyes glued to my every move, it hit me that she thought I was there to steal. It didn't matter how I was dressed - I remember I was wearing an olive linen dress, $50 Rainbow flip-flops, and a Marc Jacobs purse - I was perceived as a threat. My cellphone rang and I began to reach into my purse to get it. Before I knew it, she swooped in, grabbed the merchandise out of my hands and yelled over her shoulder as she ran to the front of the store "if you actually want to buy any of these items, they will be behind the counter."

That same night, I went out to eat with an Asian friend. We were studying for the bar together but decided to take a break. My friend was wearing sweats and a "Wake Forest" hoodie and I was still in my olive linen dress. We both paid for our meals with credit cards. When the waitress returned, she handed my friend her check and then looked at me and asked, "Can I see your ID?"

It wasn't the first time I was carded when others with me were given a pass. During my years at Columbia Law School, I was routinely singled out and asked by the security guard for my student ID when I entered the law school building, even when I was entering the building with friends (at whom the guards would just smile and nod).

Since graduation and passing the bar, I am routinely confused with secretaries, law clerks, and court reporters. At one point, I avoided questions about "Yale!?" and simply told people that I went to school in Connecticut - not correcting them when they responded with a smug smile - "Oh, the University of Connecticut."

Being black in America is tiring and terrifying. I have two children. Both times my husband convinced me to wait until birth to find out the gender. Both times I prayed, "Please, God, let my baby be healthy. If it is a girl, please help her to have €˜good hair' so she won't be made fun of [as I was]. If it is a boy, please let him be light-skinned [like me] to reduce the chances he might be viewed as a threat and murdered."

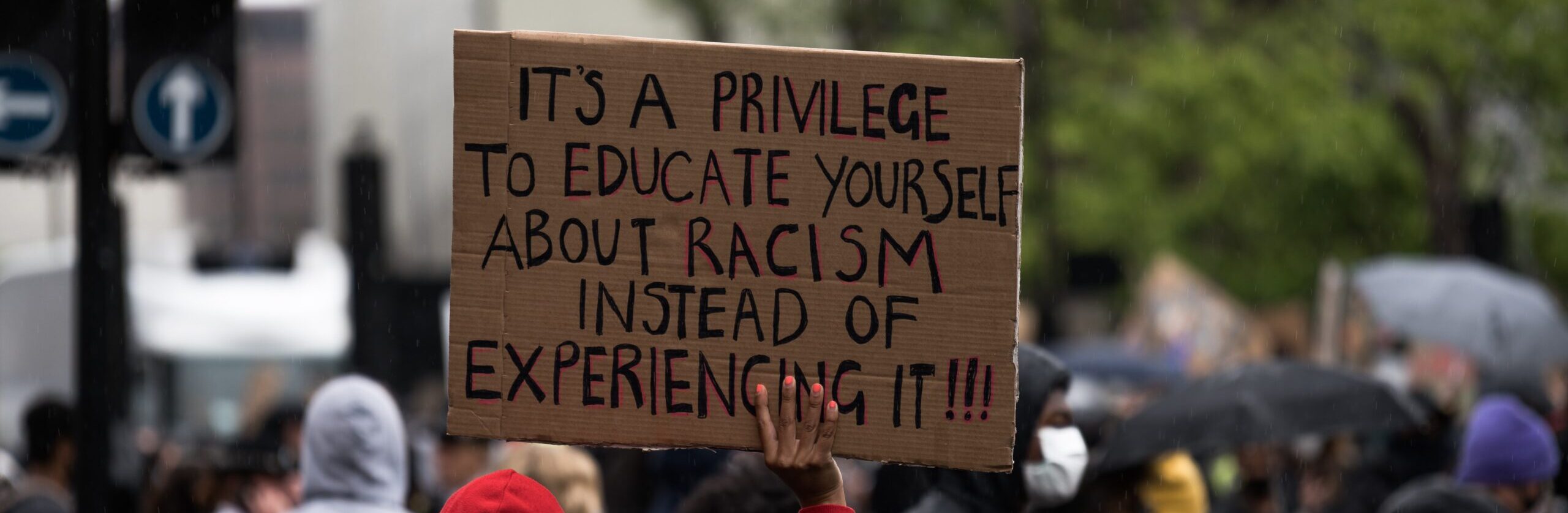

Sadly, my experience is not unique. While black Americans are not a monolith, the treatment we receive from our fellow countrymen is. I acknowledge, and am extremely grateful for, my privilege. Yet, even my privilege has not shielded me from constant reminders that my blackness is viewed as inherently inferior to whiteness. We are at a turning point in society. America is starting to ask necessary questions and to listen to and learn from the experiences of black Americans. Let us not fail the moment.

As we contemplate the best ways to move forward, I encourage the following:

1. You don't know what you don't know: While you may have grown up with and/or have close friends who are black, you don't - you can't - know what it is truly like to be black in America. I have seen multiple white friends on social media opine on the black experience - some who downplay the lasting effects of enduring years of prejudice. It is insulting to those who have lived through trauma for you to presume you know how they feel. You don't. So, stop.

2. Talk about it: For too long, we have refused to talk about race. Southerners always joke that there are certain topics - like religion and politics - we just don't talk about in polite company. This must change.

3. Listen and learn: We must have difficult conversations - even if they make us feel uncomfortable - in order to move forward. Listen to what others have experienced and how it made them feel.

While 2020 has been a bear of a year, I am more hopeful that the world my children will grow up in will be more fair and equitable. This is America's moonshot. We have been given chance after chance to make this country a true land of opportunity for all. We failed at its inception, before the Civil War, during Reconstruction, through Jim Crow, and into the Civil Rights Movement. Each time we gave lip-service to change without doing the requisite work to atone for our sins and take action. Here is our opportunity to affect the change older generations merely dreamed of and our founders claimed they intended with the words: "[O]ne nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all."